Interpretation

The major predictions that participants primed to feel self-uncertain (as opposed to “certain”) would be more cohesive (i.e., willing to work through a hypothetical cost-benefit decision) with (H6) dissimilar people who clearly mostly agree on the higher risk/higher payoff choice over those that do not seem to have a clear preference or prefer lower risk, and (H5) similar (on task-irrelevant traits) people who disagree over dissimilar people who disagree were confirmed by one study. Participants asked to think about feeling more self-assured did not show any differences in any measure of connection to or warmth toward the group no matter if the rest of the group were similar in terms of personality or clearly mostly agreed about the course of action they would choose. The only predictions related to traditional measures of social identification that were corroborated were that, ignoring uncertainty, participants would identify more with groups similar in personality and that agreed (in the case of groups clearly preferring the risky course of action). No predictions regarding entitativity including that changes in this measure would mediate the relationship between at least personality similarity and identifications were confirmed. The results provide clear support for the idea that self-uncertain participants in dissimilar groups prefer a clear norm and some evidence for a sort of risky shift when it comes to people’s preference for a clear risky rather than cautious prototypical position was confirmed. Further evidence for the latter is the fact that the lowest mean, 3.75, denotes an average response just below the midpoint or leaning toward switching groups but close to indifferent, so the only participants who actually, on average, wanted to switch groups, were self-uncertain participants viewing personality-diffuse groups who mostly wanted Mr. L to take the cautious route, thought at least one alternate explanation exists. The participants who wanted to switch groups were those in the self-uncertain, dissimilar, agreed-cautious condition of the study, showing a sort of additive effect where caution and dissimilarity together made working with the group least enticing.

One study testing whether priming the concept of uncertainty would lead to higher identification with non-interactive groups expecting to come to a collective decision (i.e., combine preferences) either when the group is described as being similar in terms of personality and preferred choice in a cost-benefit scenario is reported. The most central hypothesis left unfalsified, is that uncertain participants in a group described and illustrated as personality-homogeneous would identify equally regardless of pre-discussion preference distribution and if personality-diffuse groups would identify more with a group with a skewed (toward risk over caution) preference distribution. That is to say, it was predicted that within similar groups people self-uncertain would prefer agreement but there were no differences in cohesion among people uncertain viewing homogeneous groups. Still, personality and preference distribution both predict identification on the continuous measure, with homogeneity and skewed distributions corresponding to higher identification, regardless of participant level of self-uncertainty, suggesting that uncertainty in combination with being in a task-oriented group shifts people’s assessment of a group away from personal involvement and to considerations of potential task or process conflict. The lack of counterbalancing (dis)similarity and (dis)agreement manipulations, which could alone explain the asymmetry of differences between preference distribution conditions between similar and dissimilar groups, was to ensure the task parameters, the thing that there was agreement or disagreement on, were still in mind when participants were asked if they would be willing to stay with the group they were ostensibly in. It is simply a question for future research to assess whether the same lack of differences between (dis)similarity conditions would arise if participants first saw a group with a clear norm.

Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) showed a pattern of statistically different means suggesting that participants viewing similar groups did not identify less with disagreeing groups than with agreeing groups and that when presented with a dissimilar group, participants identified more with groups that agreed on the riskier of two hypothetical options over a disagreeing group. Furthermore, dissimilar, risky-skewed and dissimilar disagreeing groups were more attractive to participants than dissimilar, cautious-skewed groups, possibly confirming that risky norms and similarity independently bolster the uncertainty-reducing potential of identification with decision-making groups. Dissimilarity followed by agreement on the cautious option showed the least identification compared to all other conditions, including similarity followed by viewing a cautiously skewed preference distribution, and among disagreeing groups, similar groups were more cohesive than dissimilar ones. These results support uncertainty-identity theory and SCT’s predictions in the novel and more specific context of decision-making groups and comports with previous findings of evaluation of undecided groups (members) being higher if the member is otherwise non-threatening or disagrees with an category-congruent norm (a priori assumed valid opinions being category-congruent in preference combining groups; Somlo, Crano, & Hogg, 2015). Furthermore, this research is a novel test of whether perceiving risky norms over just a norm reduces uncertainty through identification, at least when operationalized as intention to interact with a group, more effectively than cautious norms. Additional work should test whether cautious norms are perceived differently than risky norms by self-uncertain people in terms of how certain others who follow or create these norms are; whether caution is akin to being nonnormative in some cases not because the population leans risky but in certain contexts caution is seen as simultaneously validated by consensus but a consensus of people without strong personal opinions where, as in decision-making or discussion groups, opinions need to be justified and cautious norms being less controversial but thus supported less by strong arguments.

The predictions and interpretations rest on the assumption that when uncertain, people’s identification (or cohesion in a task group) will track with the previously observed tendencies toward following norms, that underlying all of these tendencies is a need for clarity of purpose, action, and thought, especially (or only) if the group lacks any traits that support entitativity perceptions. Theory suggests prototype-based comparison is necessary for identification to reduce uncertainty, empirical evidence prior to the present research shows it is, but only conclusively when a group is perceived as entitative. These results, given they only fully confirm predictions for the behavioral, social distance-type measure of identification, really suggest task uncertainty, which is inextricable conceptually from self-uncertainty at least when considering priming self-uncertainty prior to possibly completing a judgment task with strangers, or some hybrid of the two related to perceived potential inefficiency on a task with a social and objective component is being reduced in more cohesive participants.

Limitations

Outside of the entitativity-relevant predictions, the major unverified prediction is that among self-uncertain people viewing similar groups, there would still be significant differences between preference norm conditions. The present research was mainly designed, however, to look at what would happen in absence of traits furnishing a perception of entitativity. One could reasonably raise the objection that no hardline predictions were made for whether there would be differences between preference distribution conditions when the group is similar and participants are self-uncertain, and to address this objection one might point out that a prediction of no differences between self-uncertain participants viewing similar groups does not contradict predicting a different relationship between preference norm conditions in terms of cohesion when comparing participants assigned to view dissimilar groups. Furthermore, the results could appear to indicate that one or the other, intra-group similarity or skewed preference norms, are enough to reduce uncertainty on their own, however without counterbalancing (i.e., people always saw personality test score distributions first so no test of whether agreement presented first would have led to there being no difference between dissimilar and similar groups is possible with this data) one can only say that task-irrelevant similarity is sufficient to render the differences between agreeing and disagreeing groups null, but the opposite cannot definitively be said. Similarity could be a bigger predictor of cohesion and a study that presents preference distribution information first to half of participants is needed to really nail down the relative importance of these two variables.

A second valid criticism of my analysis: statistically significant differences at least in a meaningful pattern relevant to my hypotheses are all but undetectable without controlling for gender, which was only marginally (greater than five percent and less than or equal to ten percent likely to be caused by regular variation in the sampled population) significantly correlated to entitativity. However, no other participant characteristics even marginally correlated with our outcome measures, so this is either evidence of fishing for results (as there is no empirical evidence as of yet to suggest men or women should perceive groups as more or less entitative based at least on how clearly a skewed normative preference exists) or controlling for an important covariate in our particular sample. Specifically, this research has revealed it may not be perceived entitativity that always makes a group a better candidate for uncertainty reduction in the decision-making context and more work needs to be done to see if process-wise it is really the distance to consensus or the likelihood of there being a verifiable normative preference explaining willingness to stay in a group. A major qualifier of research into identification with artificially created and ‘one-off’ task-oriented groups is leading people to feel a part of a group while trying to control for whether they feel personally similar or agreed with a group in the way other members are described as being similar or in agreement and measuring perception of and preference for such groups in a manner that makes sense for the context. The border condition on the relationship between entitativity or underlying group traits and identification under uncertainty may be in the decision-making domain where being asked about identification with others in a potential one-off interaction may make less sense than asking about willingness to work with the group and other factors that should correlate with but are not the same as social identification. Hence, these results really only proved predictions for the cohesiveness measure more than the traditional measure of social identification.

There are several explanations related to uncertainty reduction for why a risk-skewed preference norm would be preferred over just having a clear preference norm. While there may be no tendency toward risk in the population there is the finding in the polarization literature (a subset of the decision-making literature) that when a task involves giving advice to someone else rather than choosing a course of action for one’s self or a friend, as in the present study, people tend to choose riskier options because they are not personally invested in the outcome (Laughlin & Earley, 1982). The original motivation for the present study was to see if especially when self-uncertain and more in need of group clarity identification follows people’s tendencies toward upholding common opinions and information in the decision-making context. An alternative explanation of the present results still fitting with an uncertainty-identity theory analysis is that self-uncertainty leads to a preference for groups that follow society-wide tendencies that participants know of. Indirect evidence of this comes from the fact that statistically controlling for participants’ actual choice preferences renders all predicted and observed differences nonsignificant, even though the frequency of different participants preferences were evenly distributed across experimental conditions implying personal preference somehow mediated the relationship between group traits and cohesion but it may not have mattered if participants themselves agreed with group norms, but rather whether the group norm made sense in a larger societal context. That is, most people have a sense that the most common response will be risk given a hypothetical situation or they knew it was intuitively irrational and wanted to convince their group against taking a risk. A third explanation is that cohesion indicates how badly participants wanted to correct their group members and take the reins to reduce their own uncertainty. Either way, cohesion was higher among dissimilar people agreeing and agreeing on risk and this 66was only the case in self-uncertain participants, generally suggesting at least uncertainty is reduced for one of these reasons by agreement on the normative response among dissimilar groups.

The present research decidedly provides no test of how much participants actually felt they belonged to their groups based on their CDQ response or their responses to the three “personality” measures, if the research design did not satisfactorily account for this by having all groups with at least one person choosing each response option and it being impossible to calculate whether their scores were included in the scatterplot of the group’s. There should have been no differences in how represented participants felt between personality similarity conditions also because both graphics in dissimilar and similar conditions depicted a somewhat evenly distributed group of respondents, one just being more spread out than the other. The only glaring departure from predictions comes when looking at entitativity, and can either be attributed to measurement issues, that only one aspect of entitativity was manipulated, or that both personality conditions appeared equally homogeneous just more or less diffuse and choice preference has nothing to do with entitativity. Issues with the entitativity manipulation check measure itself include that items were not more tailored to the experimental context for example by specifically asking if groups appeared to have different or similar personalities, and the entitativity measure was made up of two extant items and one adapted and different response scales, which seems to have alone been enough to render the three items together less reliable a measure than a scale using the two copied items.

Conclusion

The question remains, what the application of these results to less constructed and artificial contexts is. The major implication of this research is in the organizational and institutional context where people need to often work together in teams to achieve the organization’s goals in part and that training is imperative to reduce task-relevant uncertainty and performance anxiety, which can be related to self-uncertainty. This type of anxiety leads people to take short cuts and unless the group is homogeneous, which put constraints on group composition, they will take short cuts to agreement that do not necessarily yield the best results.

Similarity and agreement have been manipulated in the context of many studies (see Isenberg, 1992) but not in the presence or absence of self-uncertainty. Also, no works to date besides the present work have looked at perceived potential conflict in potential discussion groups in relation to self-uncertainty. Similarity and agreement are two things that give the appearance that a task group mostly have the same preference and otherwise would get along so coming to a single collective choice that most people could personally get behind.

In an explicit decision-making situation, self-uncertainty may be more relevant to judgments of how the group will complete its task rather than personally feeling connected or attached to groups created for a purpose. Furthermore, just the presence of a norm or similarity are enough to address the need for self-uncertainty reduction, the direction of the norm being what most people in the given experimental context would prefer or can be argued against or for most easily rather than specifically risky norms providing a prototypical position. Uncertainty may lead people to focus more on assessing whether consensus can be reached and less on the quality of a decision as it caused differences in cohesion and not in identification that is typically more related to feeling positive towards group members. To this point, it should be noted that people opting for staying with the group were opting out of new groups they would know nothing about, increasing uncertainty. Still, the prediction that participants would appear to devalue a cautious norm under uncertainty is not falsified and taken at face value results confirm at least in this context, opting toward risk, perhaps only because of a ‘why not?’ thought process that is more efficient than actually worrying about what could happen to a stranger or made-up person in a hypothetical scenario, rather than risk signaling attitude certainty or more rigid group definition (though all of these explanations could be at play).

Future work outside of more rigorous replications of the present research would do well to look into teasing apart these different certainty-relevant motives and could emphasize participant characteristics and motivational factors like vested interest in the choice scenario play into their identification with groups with different preference or attitudinal distributions. Of specific interest is how participants’ own attitudes and opinions change their reactions to groups, as well as whether their own attitudes or preferences change after interaction with or learning about a group. It would also be useful to re-run these studies but counterbalancing or playing more with the ordering of stimuli as an independent predictor, tightening up the measures, using actual face-to-face groups, and manipulating the extent to which different aspects of a group or group members being evaluated are explicitly related or left independent. The present findings also suggest future research designed to look at leaving participants in the low uncertainty condition un-primed so to speak or looking more at situations where people’s social identity-relevant needs are met.

The implications of research on the effect of social identification needs, group characteristics, and willingness to work through decisions collectively, especially in contexts like jury deliberations where groups are instructed to consider all relevant evidence, but other preference combining contexts like voting and topics like voter turnout, is clear. Groups do not always benefit from addressing nonnormative opinions in terms of decision quality, but if there is no pathway to communication and groups in disagreement are avoided, they may be unable to come to a collective decision or one that represents even the majority’s interests at all. Furthermore, outside of the context of groups that will only interact once, and given most decisions are subjective and do not involve doomsday scenarios but choices corresponding to a spectrum of consequences from tolerable to ideal, one must balance group cohesion and the desire for less member turnover with decision “quality.” As political polarization seems to increase and each generation feels theirs is most precariously standing on the precipice of an uncertain future, if these fears are not mitigated, people will tend toward ideological clarity perhaps at the expense of sustainable social organization. This research is not related to the topic of valuing tried-and-true solutions or trusting social consensus when it would behoove people to do so, it is more objectively, save the preceding sentence, about the contexts where people are more likely to desire to be in a group with a clear consensus, whether it be misguided or not.

Figures

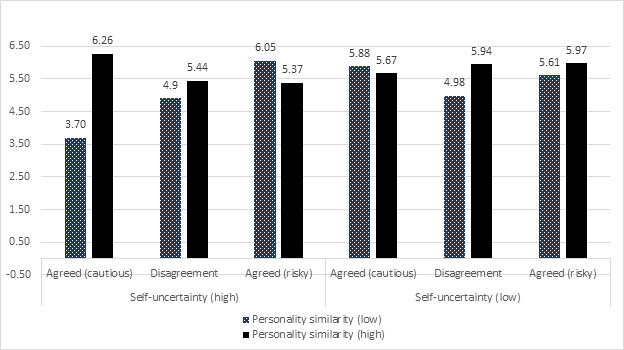

Figure 1. Group cohesion as a function of self-uncertainty, personality similarity, and the presence (i.e., agreement) or absence of (i.e., disagreement or ambivalence) a clear majority-supported group preference for how to respond to a risk-versus-caution scenario.

Of note are the three (patterned fill) low similarity or dissimilarity columns with respective means 3.7, 4.9, and 6.05 in the high uncertainty section of the graph, all statistically significantly different from one another, ts > 2.08, ps < .05, compared to the corresponding (solid fill) columns that do not significantly differ, and the most extreme difference in cohesion being between dissimilar, 3.7, and similar, 6.26, groups viewing agreed cautious groups after being primed to feel self-uncertain.

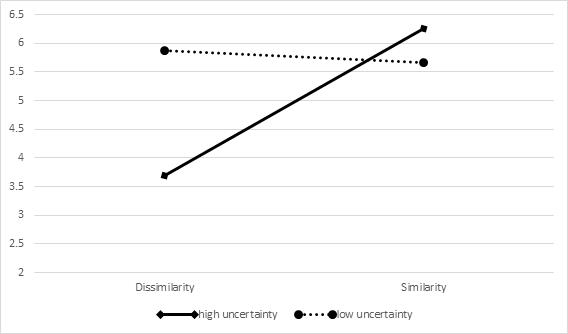

Figure 2. In-group Cohesion as a Function of Self-uncertainty and Personality Similarity among Participants Viewing Groups with Skewed-Cautious Preference Norms/Distributions.

This is to illustrate using the most extreme case the greater magnitude of mean differences between experimental conditions among participants primed to feel self-uncertain as opposed to those who were not.

Tables

| Disagreement | Agreed (risky) | |

| Similarity | 5.44a | 5.37 |

| Dissimilarity | 4.9b | 6.05c |

Confirmation of the prediction that self-uncertain participants would prefer to stay with groups that are more likely to find consensus through discussion in light of a clear and skewed preference norm or intra-group similarity, especially when the group is otherwise and respectively described as agreeing or being dissimilar to one another. Numbers with different subscripts are significantly different at least at p < .05.